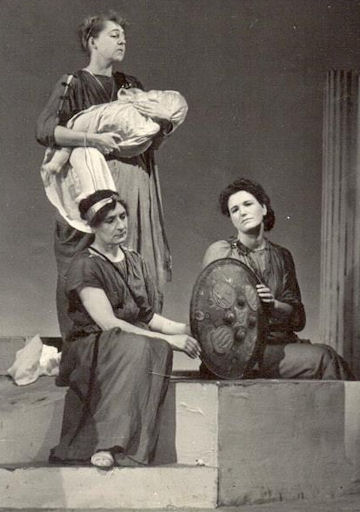

Cast:

Philip Allen, Diana Benn, Bryan Blake, Ann Cheetham, Doreen Coates, Madge Dolman, Helen Entwistle, Enid Gibson, Joyce Grant, John Howard, Tony Hunt, Muriel Landers, Elizabeth Oddie, Patricia Perfect, Peggy Pope, June Sibley, Frank White

Production Team:

Archie Cowan, Alfred Emmet, Peggy Fancet, Albert Gibbs, Mike Golding, Barbara Hutchins, Gerry Isenthal, Diana Kelly |