PRESS CUTTINGS:

Three One Act Plays (1930)

THE ROAD OF POPLARS, POSTAL ORDERS,

TWO GENTLEMEN OF SOHO

[West Middlesex Gazette, 22 November 1930]

THE AMATEUR STAGE

ASCENT OF THE QUESTORS

Tremendous Improvement on Previous Work

If The Questors progress at the rate they have during the past year, they will soon be the leading amateur dramatic society in Greater Ealing.

In giving three one act plays at the Park Theatre, Hanwell, on Wednesday and Thursday, they showed that they have improved out of all knowledge since their last production and as all but two of those who took part are under 25 years of age, it is probable that their forward movement will know no bounds. Nothing succeeds like success and when youth succeeds its ambition becomes limitless.

That The Questors did so well on Wednesday and Thursday was the more remarkable because two of the works they chose for production are very exacting. And on Wednesday, when I saw them, they were under the handicap of playing to an unresponsive audience. The effect of this upon those on the stage needs no elaboration.

APPRECIATION LACKING

This lack of response was most noticable in Two Gentlemen of Soho, a clever modern satire written in Shakesperean style. The greater part of the audience seemed unable to make up its mind whether to take the work seriously or not and dozens of piquant lines were allowed to pass without the slightest sign of appreciation. The Road of Poplars also had the audience guessing. There was a decided lack of attention, but not because the players did not capture the correct atmosphere or effect. It was simply that those looking on could not understand the war-shattered minds depicted by the author. And in view of the chattering of some people in the theatre concentration was almost impossible. It is a pity that all those who go to theatres do not play fairly by their fellows and those trying to entertain them.

It might be argued that The Road of Poplars was an unsuitable choice for production by those too young to have fought in the war and therefore unable to understand its effect upon those whom it claimed. To this The Questors have an excellent reply. From the start, they say, they recognised the difficulties of this play but preferred to attempt something exacting rather than something easy. In short, they aimed high and their ambition is to be applauded.

AN ENEMY BULLET

The Road of Poplars shows two soldiers back on the battlefields four years after the war. One, who was a Tommy, is mentally affected and sees at night those of his comrades who made the supreme sacrifice and talks with them. The other is an ex-officer who made a mistake which caused most of his company to be killed by the enemy. He, too, sees the Tommy's vision and joins those who have passed over. It is an enemy bullet that sends him amongst them—an enemy bullet fired by the Tommy.

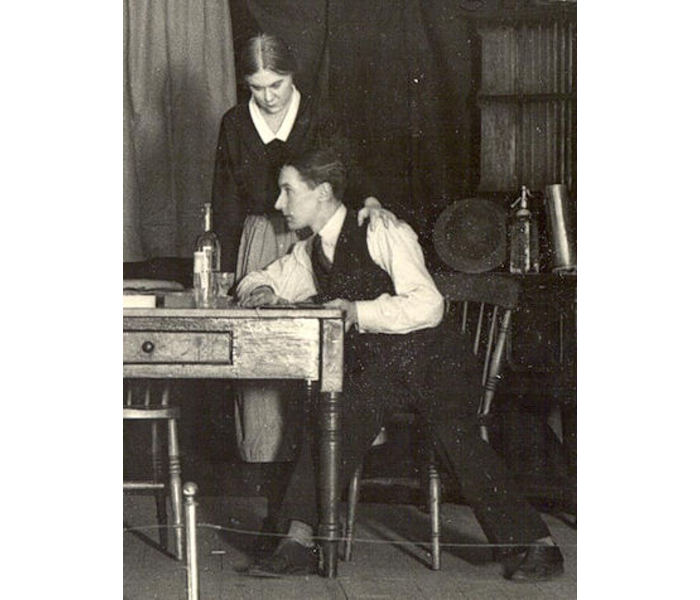

There are many opportunities for depth of interpretation and they were taken. Alec Payne, as the ex-officer, created a reputation for himself in one stroke with a display of which any amateur could be proud. His power was the same whether lie was restrained or loudly emotional — and the part is one which calls for an actor who can be convincing in both moods. As the Tommy, John Ruth played with the deepest sincerity. The way he gave the impression of straining every nerve to keep from the wild outburst to which he eventually gave way was a masterpiece of amateur acting.

There are many opportunities for depth of interpretation and they were taken. Alec Payne, as the ex-officer, created a reputation for himself in one stroke with a display of which any amateur could be proud. His power was the same whether lie was restrained or loudly emotional — and the part is one which calls for an actor who can be convincing in both moods. As the Tommy, John Ruth played with the deepest sincerity. The way he gave the impression of straining every nerve to keep from the wild outburst to which he eventually gave way was a masterpiece of amateur acting.

About the others it is possible to generalise to this extent: they realised just what kind of touch was required and applied it. In the case of Norah Hadley (the ex-Tommy's wife) it was a light one; in the case of Phil Elliott (the spirit of a soldier) a suggestive rather than solidly definite one; and in the case of Alfred Emmett (customer at an estaminet) a breezy one. The tenderness of Miss Hadley was delightful to watch.

HARDLY A LAUGH

Two Gentlemen of Soho, the work of A P Herbert, is a playlet in a class by itself. The curtain rises with an obviously burlesque police officer in obviously burlesque evening clothes bemoaning the fact that although he has haunted a night club, he cannot detect a breach of the drink laws. This should have settled once and for all in  the mind of the audience the question whether the work was serious or not, but it did not and even the baldest humorous lines, such as "How like a military balloon she looks" (in reference to a Duchess) hardly raised a laugh. Even eight successive suicides and the stage strewn with bodies puzzled rather than amused. Again the artistes were not to blame, for though they did not extract the whole meaning of their material, they extracted as much as could be expected possibly more. Philip Woollcombe, as the policeman, soon showed that be had got the spirit of the thing. This meant a realisation on his part that he had to say the most ridiculous things ponderously and seriously. The same sort of thing is required of most of the others who play in Two Gentlemen of Soho. The eight Questors taking part all had the right idea, notably Molly Harvey and Alfred Emmet, while Glen Francis showed a lot of artistry in playing the part of the waiter. Good support came from Doreen Barnard, Guy Hadley, Margery Stretton, and Frank Cockburn.

the mind of the audience the question whether the work was serious or not, but it did not and even the baldest humorous lines, such as "How like a military balloon she looks" (in reference to a Duchess) hardly raised a laugh. Even eight successive suicides and the stage strewn with bodies puzzled rather than amused. Again the artistes were not to blame, for though they did not extract the whole meaning of their material, they extracted as much as could be expected possibly more. Philip Woollcombe, as the policeman, soon showed that be had got the spirit of the thing. This meant a realisation on his part that he had to say the most ridiculous things ponderously and seriously. The same sort of thing is required of most of the others who play in Two Gentlemen of Soho. The eight Questors taking part all had the right idea, notably Molly Harvey and Alfred Emmet, while Glen Francis showed a lot of artistry in playing the part of the waiter. Good support came from Doreen Barnard, Guy Hadley, Margery Stretton, and Frank Cockburn.

A HARDY FARCE

That well-known farce, Postal Orders, was also given. Evelyn Skelton, Barbara Sharp, and Margaret Browne were good as the post office ladies, and Hilda Elliotthandled the part of the customer well; but Alfred Emmet spoilt himself somewhat by allowing his voice to drop when he had his back to the auditorium, giving the impression that he was conducting a confidential back-stage conversation. Alec Payne produced well and overcame, in a large measure, the difficulty of having only the plainest of settings.

LJD

[THE MIDDLESEX COUNTY TIMES, 29 November 1930]

A TRIPLE BILL

THE "QUESTORS' " SUCCESS

The Questors, who gave as their third production in the Park Theatre, Hanwell, last week, three one-act plays, are the youngest (in all senses) of the group of local amateur dramatic societies in these parts, and they are well-named, for questing is in their blood. Like Columbus, "'They cleave a passage by force of will and faith rather than by grace of reason.•" Intrepidity and a desire to try out new routes on dramatic seas, as yet uncharted, replace caution and experience which are the more usual guiding stars of amateur companies. It was this spirit of enterprise that induced them, undaunted by its obvious difficulties, to be the first amateurs to produce Vernon Sylvaine's The Road of Poplars, which, out of some 4,000 plays, won the John o' London one-act competition last summer, and was singled out by Mr. St. John Ervine as easily the best one-act play he had read for many years. Of the literary and psychological appeal of this post-war play, set in the parlour of an estaminet on the Menin Road, near Ypres, there can be no two opinions, but to catch and transmit across the footlights its intensity and refinement of feeling, expressed throughout in a definitely minor key was a task which might well have daunted societies of maturer experience than The Questors.

On its purely human side the venture was more than justified. The mortals of the cast "lived' ; they were, as the older folks who looked on knew, men of flesh and blood, with red-hot, war-torn and tortured memories, men ho had felt and suffered, and suffered still. The vibrations which the play set in motion were stingingly sincere. Both the play and the principal players— Mr. John Ruck as Charley, the ex-service Englishman. the "fou" husband of Marianne and utility man at the estaminet, and Mr. Alec Payne, as the English ex-officer—held the audience, even those among it who did not altogether understand and perhaps vaguely resented the choice of play. Both-actors were skilful in tragedy, but each kept his place; therein lay the secret of the success of the production. Never once, though they met on a common ground of vivid war-memories, did Mr. Ruck's Charley cease to be the whimsical, wistful, war-haunted, intuitive soul in trouble, receptive of psychic influences, almost more at home with the ghosts of his fellow soldiers than with tho customers whom he daily served with drinks. Never once did Mr. Payne's study of the officer who had mis-read the directions and so led his company to slaughter cease to suffer as a disciplined stoic, a rugged exterior hiding torture of remorse that was almost unbearable. The contrast was sharp throughout, though the sympathy that hound the two men together was consistently emphasised. The remaining three human characters are all minor, but each in its degree rontributed towards the "getting-over" of the play. Miss Norah Hadley's Marianne was true to type—a compassionate, maternally minded French peasant, very tender to her half-foolish husband, but understanding not at all hi deeper longings and nature. Her French was dainty and excellent in intonation. Mr. Alfred Emmet portrayed the excitable little French chess-player in just the right key and Mr. Philip Woollcombe's appearance in the part of "another customer" was all too short, for he was excellent.

The purely supernatural portions of the play, the ghostly march of the dead army, the appearance in the estaminet doorway of the astral form of Richardson (adequately played by Mr. Phil Elliott). the death of the English officer and the dragging off of his body, were rather less convincing, but these required a deeper stage.

A CURTAIN-RAISER CARICATURE

Even when the curtain finally fell upon a stage on which were lying in various decorative and undecorative attitudes of simulated death all the eight characters in A. P. Herbert's Two Gentlemen of, Soho, the audience had hardly made up its mind about this play, with its strange jangle of gibberish expressed in mock-heroic blank verse. This play, which formed part of "Riverside Nights" at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, has its definitely strong and weak points. It is a dramatic gargoyle, a nightmare hybrid of burlesque and caricatured Shakespeare, particularly of "Hamlet" and the "Two Gentlemen of Verona." It demands specially fine team work, and this was forthcoming. Sense inculcated by nonsense, and truth emphasised by exaggeration, is the message of the play, and in this direction remarkably fine studies in extravaganza were given by Mr. P. Woollcombe and Mr. Alfred Emmett, as Plum and Lord Withers and by Mr. Glen

Francis as the waiter. Miss Doreen Barnard contrived to look a night-club habitué, charmingly naughty haughty and nonchalant, and Miss Molly Harvey as Lady Laetitia was even prettier in death on the divan than in life, which is saying much. Miss Margery Stretton's Duchess of Canterbury was a clever burlesque of a would-be young old hag. The other characters wore excellently taken by Mr. Frank Cockburn and Mr. Guy Hadley.

A POSTAL COMEDY

Roland Pertwee's one-act fare, Postal Orders, was an excellent opening to the programme, for it made everyone laugh and gave Miss Evelyn Skelton, Miss Barbara Sharp, and Miss Margaret Browne an opportunity of showing (as a trio of dilatory postal officials) what good comedy actresses they can be. They played up to each other loyally, and Mrs. Hilda Elliott and Mr. A. Emmett as irritated members of the general public with very personal affairs at stake completed a well-rehearsed. and efficient cast. The farce went briskly as it should.

Such a programme as The Questors presented imposed a heavy burden upon the producer but Mr. Alec Payne was fully alive to the difficulties he had to combat, and be received loyal help from Miss Margery Stretton and Mr. A. Emmet. Mrs. Kathleen Payne was stage manager and Mr. Phil Elliott and Miss Christine Blackwood assisted her.

Agreeable incidental music was played by an orchestra under the direction of Mrs. Talbot-Barnard, the members being Mesdames Winnall, Mackenzie, Kennett, the Misses Havelock Davied, Gammelien, Gardner, H. Grice and Mathews, with Mr. T. Watson.

CC