PRESS CUTTINGS:

A Bill of Divorcement (1931)

[MIDDLESEX COUNTY TIMES. 11 April 1931]

A PLAY THAT MAKES YOU THINK

Ealing Players' Success in Problem Drama

True to their policy of forsaking the beaten paths where sheep "chew the cud" of dramatic grass contentedly with  no thought of or wish for adventure, The Questors, now only in their second season, again set out to find a play to make themselves and their audiences think. Their choice fell upon Clemence Dane's three-act problem drama, A Bill of Divorcement, first produced at St. Martin's Theatre, London, in the spring of 1921.

no thought of or wish for adventure, The Questors, now only in their second season, again set out to find a play to make themselves and their audiences think. Their choice fell upon Clemence Dane's three-act problem drama, A Bill of Divorcement, first produced at St. Martin's Theatre, London, in the spring of 1921.

The period is Christmas Day, 1933, when a majority report of the Royal Commission on "Divorce v. Matrimonial Causes" has become the law of the land, and the wife married to a husband who has been insane for over five years, and whose case is regarded as hopeless by the medical profession, is free to marry again. Those who like A Bill of Divorcement —and it is technically one of the finest plays written by a woman playwright—and those who do not, agree that the play chains interest and releases thought.

One may argue that the characters presented are the result of the circumstances in which they find themselves, that the circumstances are the result of the actions of the characters, and that the problems introduced, and which re act on both, take their rise from either or both sides. But, consciously or unconsciously, one thinks and argues. It is a play which is impossible to see and to "straightway forget what manner of play" it was. It would remain a great play, well or badly acted, and it was far from being badly acted by The Questors at St. Martin's Hall, West Acton, on Thursday and yesterday evenings. If the production lacked a little of the fine polish and artistry which marked The Road of Poplars, it rang true in all the essentials of intellectual grasp, understanding and sincerity, significant things which made a few minor blemishes of detail—in make-up, stage doors which opened too readily, and noisy curtains—seem of small account.

TRIUMPH OF ACTING

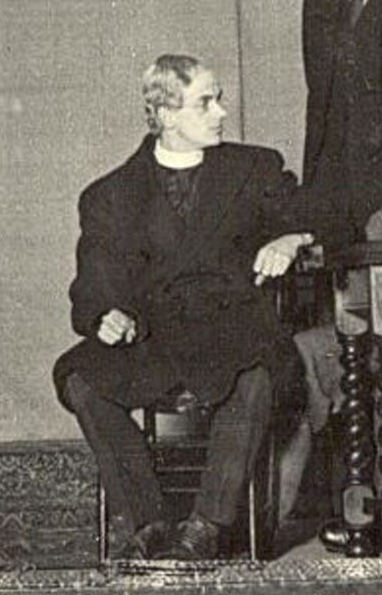

Mr. Alec Payne's acting as Hillary Fairfield, the still nervy but no longer insane  husband, whose sudden return causes such a "bombshell," was a triumph of sincerity. It combined strength, weakness, passion, plaintiveness, pathos, tragedy; each was uppermost in its turn, and always in the right proportion. Mr. Payne, who was also the producer, gave a study as Hilary which ranked with his "tourist" in The Road of Poplars, and it was he who really held the cast together, by his own acting no less than as the producer. Miss Margaret Browne's acidulated study of bigoted old-maidenhood, as typified by Aunt Hester, was, perhaps, next in order of merit. Into her mouth is put one of the most signi ficant lines in the play, "Ah, we cry after the dead, but I've always wondered what their welcome back would be!" Between them, the Author and the player made Aunt Hester the diametric opposite of Aunt Gertrude in Milestones both clever portraits. When a player's personality exactly fits a part, its success is assured so long as stage fright is avoided. Miss Barbara Sharp was wisely cast for the significant part of Sydney Fairfield, the insane husband's modern daughter. It might have been written for her, so much did it seem a part of her. A certain amount of angularity and knobbiness, duty followed in grenadier-like style, with colour and courage, were all vividly portrayed, and with so complete a naturalness as not to seem acting at all.

husband, whose sudden return causes such a "bombshell," was a triumph of sincerity. It combined strength, weakness, passion, plaintiveness, pathos, tragedy; each was uppermost in its turn, and always in the right proportion. Mr. Payne, who was also the producer, gave a study as Hilary which ranked with his "tourist" in The Road of Poplars, and it was he who really held the cast together, by his own acting no less than as the producer. Miss Margaret Browne's acidulated study of bigoted old-maidenhood, as typified by Aunt Hester, was, perhaps, next in order of merit. Into her mouth is put one of the most signi ficant lines in the play, "Ah, we cry after the dead, but I've always wondered what their welcome back would be!" Between them, the Author and the player made Aunt Hester the diametric opposite of Aunt Gertrude in Milestones both clever portraits. When a player's personality exactly fits a part, its success is assured so long as stage fright is avoided. Miss Barbara Sharp was wisely cast for the significant part of Sydney Fairfield, the insane husband's modern daughter. It might have been written for her, so much did it seem a part of her. A certain amount of angularity and knobbiness, duty followed in grenadier-like style, with colour and courage, were all vividly portrayed, and with so complete a naturalness as not to seem acting at all.

Whoever is cast for the part of Margaret Fairfield, the divorced Wife, is somewhat to be pitied, but Miss Norah Hadley wrestled bravely with this pliant and plaintive  character, who drew any vitality she possessed from her daughter, her lover, or any stronger character with which she came into contact. Such a character is hard to cope with, especially when one is young, but Miss Hadley at least made it feasible, and fitted into the place allotted to it in the play. A singularly pleasant and unaffected boyishness made Mr. Eric Emmet's study of Kit Pumphrey attractive, and he was especially good in the quarrel scene with Sydney, in the last act. Mr. Phillip Woollcombe's acting, as Gray Meredith, to whom Margaret is on the point of being married, would have benefited by greater dash and a touch of the masterful male. It was, however, competently acted on rather rigid and restrained lines.

character, who drew any vitality she possessed from her daughter, her lover, or any stronger character with which she came into contact. Such a character is hard to cope with, especially when one is young, but Miss Hadley at least made it feasible, and fitted into the place allotted to it in the play. A singularly pleasant and unaffected boyishness made Mr. Eric Emmet's study of Kit Pumphrey attractive, and he was especially good in the quarrel scene with Sydney, in the last act. Mr. Phillip Woollcombe's acting, as Gray Meredith, to whom Margaret is on the point of being married, would have benefited by greater dash and a touch of the masterful male. It was, however, competently acted on rather rigid and restrained lines.

Mr. Guy Hadley as Dr. Alliott tried valiantly to assume the determinedly cheerful, professional manner of the family's medical adviser, and succeeded, although he hardly looked the part. Miss Ruth Eliott was a little amateurish as Bassett, the parlourmaid, but Mr. Alfred Emmet showed considerable acting ability as the country parson, much concerned with small matters. The silent role of the puppy was efficiently taken by "Bill" Browne.

Mrs. Kathleen Payne was stage-manager, and the scenery, rather on the austere side, was designed and executed by The Questors themselves. The intervals, admirably short, were beguiled by agreeable instrumental music provided by an orchestra under the direction of Mrs. Talbot-Barnard, and consisting of Mesdames Mackenzie, Spenceley, Hewson, Murray and Kemmett, the Misses Davies and Matthews, and Messrs. Murray and Watts.

C C

[WEST MIDDLESEX GAZETTE, 11 April 1931]

TASK FOR THE QUESTORS

Clemence Dane's "A Bill of Divorcement"

SETTING NO HELP TO THE PLAYERS

The Questors have very decided ideas as to what amateur dramatic societies should and should not produce.

They quite rightly refuse to compete with the professional stage by putting on, as some societies do, plays that have just had a long run in the West End and it is no part of their policy to identify themselves with works of little or no dramatic merit.

They convinced themselves and the public that they could cope with difficult material when they made such a success of The Road of Poplarsat the Park Theatre, and they attempted a further exacting task in presenting Clemence Dane's A Bill of Divorcement at St. Martin's Hall, West Acton, on Thursday and Friday.

One can hardly compare A Bill of Divorcement with The Road of Poplars, but I did not find the Questors so satisfying when I saw the former on Thursday as I did when I saw the latter a few months ago. Apart from the fact that it is obviously more difficult to maintain a given standard for three acts than for one, the general handling of the work suggested that the Questors had not made the best possible choice of play in view of the talent in their ranks, although it would have been difficult for them to have made a more interesting choice.

THE MOUNTING

I am prepared to admit that the mounting did not set off the Questors' work to the best advantage. They would have done better to have played in front of curtains than to use the makeshift scenery which they did, for the setting had amateur stamped all over it. The walls looked the flimsy things they were, ill-fitting doors swung open of their own accord and gave the audience a backstage view, and a window with snow scene beyond was blatantly artificial.

These things distract an audience and the players must sense a certain lack of sympathy and realise that extra effort must be made to centre attention in the things which matter rather than in those which do not matter so much. And the knowledge that this extra effort is required means that the players are going to struggle to achieve it and perhaps struggle obviously, I which is fatal.

It is probable that Miss Barbara Sharp was affected by this knowledge for in the course of what, I must admit, was a good all-round display she seemed rather concerned with things outside her own acting. At any rate, one sensed that she was not feeling very comfortable about what was going on about her.

But when Mr. Alec Payne had the stage it was possible to forget everything else. As the believed incurable lunatic who recovers his sanity he made the most of the contrasts of his part ; and carried his audience with him whether he was quietly pleading or making nervous outburst. Mr. Phillip Woollcombe played with complete conviction in the entirely different part of Gray Meredith, the man who is to marry Mrs. Fairfield, she having taken advantage of a divorce law the audience is asked to imagine has been passed and obtained a divorce on the ground of the lunacy of her husband. Mr. Woollcombe never looked the slightest bit hesitant and, on the contrary, showed such firmness that the part might have been part of his own life.

UNCONVINCING

With Mr. Alfred Emmet as the Rev. Christopher Pumphrey  an exception, those who had the parts of much older people did not convince. Mr. Guy Hadley did not look the trusted family physician and Miss Margaret Browne, judged by her appearance, was not the middle-aged spinster she was supposed to be. Incidentally, she did not make the most of her opportunities for presenting with austerity the nineteenth century outlook. Miss Norah Hadley was impressive in her emotional scenes, but failed to infuse life into the others. Most of the brightness came from Mr. Eric Emmet who was Mr. Woollcombe's equal in confidence.

an exception, those who had the parts of much older people did not convince. Mr. Guy Hadley did not look the trusted family physician and Miss Margaret Browne, judged by her appearance, was not the middle-aged spinster she was supposed to be. Incidentally, she did not make the most of her opportunities for presenting with austerity the nineteenth century outlook. Miss Norah Hadley was impressive in her emotional scenes, but failed to infuse life into the others. Most of the brightness came from Mr. Eric Emmet who was Mr. Woollcombe's equal in confidence.

The part of the servant, though small and with a minimum of speaking, could have been handled better than it was by Miss Ruth Elliott.

LJD